The climate emergency poses an existential challenge to the human rights project. The hard-won normative and practical progress that human rights movements, organizations, and institutions have made over the past seventy years is being fundamentally disrupted by the pervasive and massive impact of global warming on the planet and the societies that inhabit it.

During those seven decades, humanity also embarked on the Great Acceleration, an unprecedented period of feverish economic activity, population growth, and alteration of the conditions for life on Earth. The impact has been so deep that it will be forever inscribed in the geological record, in the form of traces of nuclear tests, pervasive fragments of our plastic products and other signals of this era that have been buried deep underneath the Earth’s crust.

This has led scientists to suggest that we are living in a new epoch of planetary history: the Anthropocene, the period during which a single species (us) gained the power to alter the fate of all other species and the planet at large.

If human rights are to remain relevant in the Anthropocene, budding theoretical, doctrinal, and advocacy efforts from within the field to address the climate emergency need to be deepened and expanded. The task of urgently advancing climate action through rights-based norms, frames and tactics is what I have called “climatizing” human rights.

There are two complementary routes to climatizing human rights. The first route involves applying the existing human rights conceptual and legal tools to the climate emergency. This route entails both addressing the impacts of global warming on the enjoyment of human rights and ensuring that climate policies follow human rights norms regarding substantive and procedural equity. Although much has yet to be done, key human rights actors—from advocacy organizations to national and international courts to UN bodies—have made important initial inroads—for instance, through a wave of rights-based litigation that seeks to hold governments and corporations accountable for climate inaction.

If human rights are to remain relevant in the Anthropocene, budding theoretical, doctrinal, and advocacy efforts from within the field to address the climate emergency need to be deepened and expanded.

The second, complementary route entails adapting and updating human rights to the Anthropocene’s realities and challenges. In addition to a concern with guaranteeing at least a minimum of individual freedoms, material welfare and equity compatible with human dignity, this goal requires protecting the planetary boundaries that make life on Earth possible—and thus entails a concern with the limits to human economic activity. Between the minimum of activity that is needed to protect rights and the maximum that is compatible with planetary boundaries there is a vast space for human activities that are productive, equitable, regenerative, and respectful of future generations and the planet.

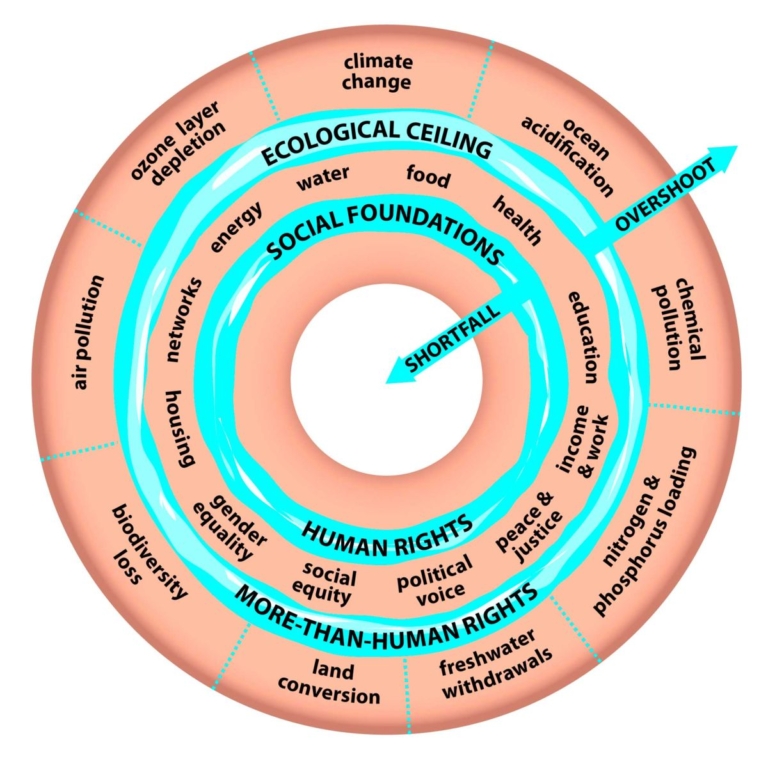

Economist Kate Raworth has usefully depicted this space as a “doughnut” (see figure below). In human rights terms, the inner ring is composed of the social foundations of human well-being as determined by civil, political, and socioeconomic rights. The outer ring is made up of the maximum pressure levels that Earth’s life systems, according to science, can bear—from climate to the oceans to forests to the nitrogen cycle to the air that we breathe. Remaining within these limits entails a concern not only with the rights of people alive today but also those of future generations and non-humans, as social scientists like Raworth and moral philosophers like Martha Nussbaum have argued.

This expanded view of rights has direct and tangible consequences for policy and advocacy. From this perspective, states, corporations and other duty-bearers should be held accountable not only for failing to meet basic material human needs but also for undermining the biosphere and the conditions that are indispensable for the continuation of life on the planet. For example, countries that may score high on economic redistribution (such as Australia, Canada, and Norway) should not get a free pass from socioeconomic rights actors to the extent that their redistributive policies are funded by oil, coal, and other carbon-intensive industries that destabilize the climate system on which their nationals and all of humanity depend.

In addition to questions about material well-being and equity, human rights actors should raise questions about the compatibility of economic policy with a liveable climate system, biodiversity, air quality, and other conditions necessary for human flourishing and a thriving web of life.

Human rights researchers and practitioners have yet to develop the battery of legal concepts, norms, and doctrines that are required by this holistic approach to rights. Insights from life and health sciences, which are increasingly focused on the similarities and interdependence between the human and the non-human worlds, provide a promising path forward toward this approach.

The evolving understanding of the right to health is a case in point. Following in the footsteps of Indigenous knowledge, ecology, and other holistic worldviews, life and health scientists and practitioners are developing frameworks like “One Health,” which stress the indivisibility of human health and ecosystems’ health and has been embraced by the World Health Organization. As shown by the twin health emergencies (and persistent threat) of climate change and pandemics stemming from the destruction of ecosystems, the right to health depends on measures to protect the health of nature.

In addition to questions about material well-being and equity, human rights actors should raise questions about the compatibility of economic policy with a liveable climate system, biodiversity, air quality, and other conditions necessary for human flourishing and a thriving web of life.

Under the conditions of the Anthropocene, defending the right to health requires going beyond a concern with present generations of humans. It entails also defending the health of the “more-than-human world” constituted by nature and future generations, to borrow the apt terminology proposed by philosopher and ecologist David Abram. In addition to present-day humans’ rights, it requires advancing what I have called “more-than-human rights,” that is, the rights of future generations and non-humans.

The articulation of this holistic approach—the second route to the climatization of human rights—remains largely a pending task. However, emerging developments in the field, especially in domestic and international rights-based climate litigation, are planting promising seeds. For instance, environmental organizations in Norway have exposed and challenged in court their government’s double standard as a global champion of human and environmental rights, on the one hand, and as a leading fossil fuel exporter intent on continuing to explore for oil in the Arctic despite the massive human rights violations associated with the climate emergency, on the other.

By adding a concern with planetary limits, climatizing rights may help decelerate human activity to a level that is compatible with the flourishing of human life in a thriving web of all life. A pandemic in 2020 and the tragic flurry of floods, heatwaves, fires, and other extreme weather around the world in 2021 should dispel any final doubts about putting climate and the environment at the core of the rights agenda—before it is too late.

This article is part of a series developed in partnership with the Miller Institute for Global Challenges and the Law at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. The series draws on contributions from scholars and practitioners who participated in the Institute’s November 2020 Conference entitled “Human Rights at a Crossroads? A Time for Critical Reflection on the Human Rights Project.”